A hundred years ago, before feminism had entered the public imagination, before homosexuality was decriminalized, before women could work in a “man’s world,” it took guts to be a woman like Elsa Gidlow. By the time she was 23, the British-born, Montreal-raised anarchist lesbian had not only co-founded the first ever explicitly LGBTQ+ publication in North America, but also published the first collection of lesbian poetry, successfully built a career as a journalist, and had become one of the most vibrant anti-war voices of the era. From her middle age until her death, she sustained an enigmatic bohemian community in San Francisco, known for entertaining an ever-rotating crowd of artists and activists. In life and in love she was a true radical, entirely unencumbered by anyone’s expectations of what a woman should be.

And there were expectations everywhere. Gidlow’s family emigrated to Tétreaultville from England in 1904, when Gidlow was six years old. She was one of six and harboured intense hostility towards the Catholic church in Quebec for encouraging women to have large numbers of children despite high infant mortality and poverty rates. Though she was highly intelligent, she knew from a young age that her gender would prohibit her from becoming a doctor, and was forced to leave school at fourteen to help with her siblings’ childcare. Her limited spare time was spent teaching herself shorthand and reporting skills and secretly submitting her writing for prizes. She was determined to “find something interesting that did not call for academic proof that I had a mind and used it.”1 Writing gave her that opportunity, and she ran towards it.

In need of a salary, Gidlow took on secretarial work at a shipping company, discussing unionization with the workers and harbouring crushes on the women in the typing pool. It was a job intended to “get the money for independence, for the opportunity to make and live poetry,” but she grew frustrated when opportunities were not forthcoming, and in 1917, wrote two letters to the Montreal Daily Star under a pseudonym.2 The first purported to be from a young woman interested in any artists’ organizations in the city; the second, an assurance that such a group existed, and that interested parties could contact the undersigned.

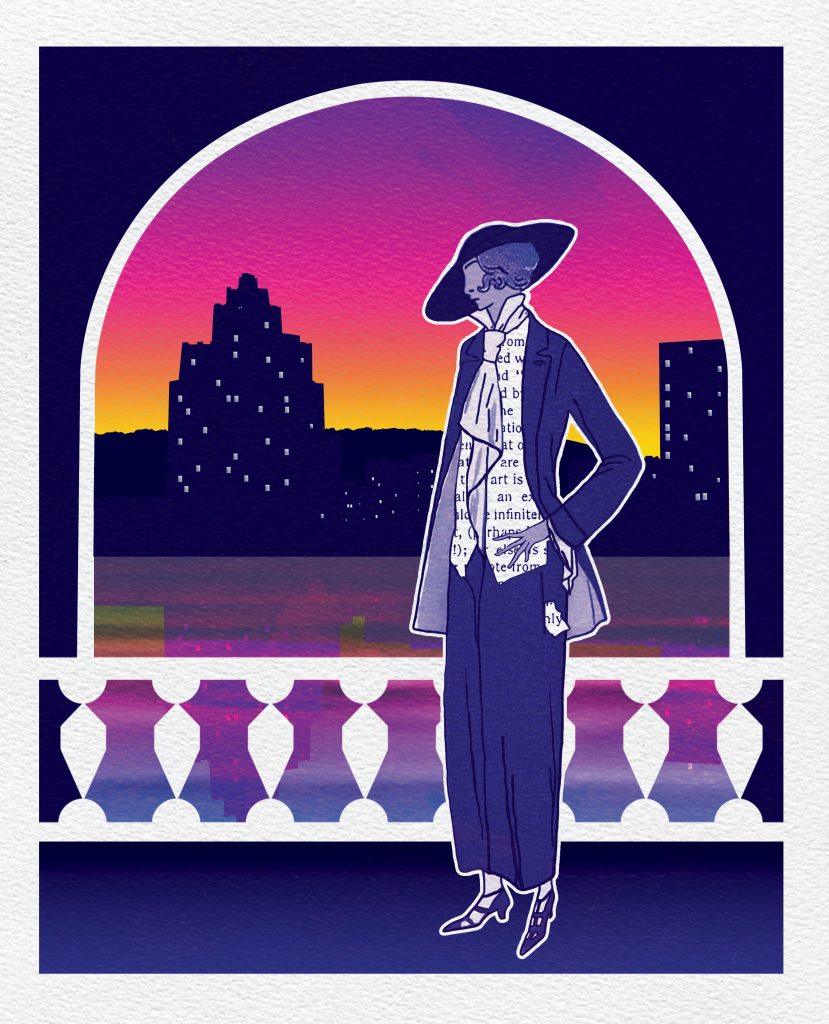

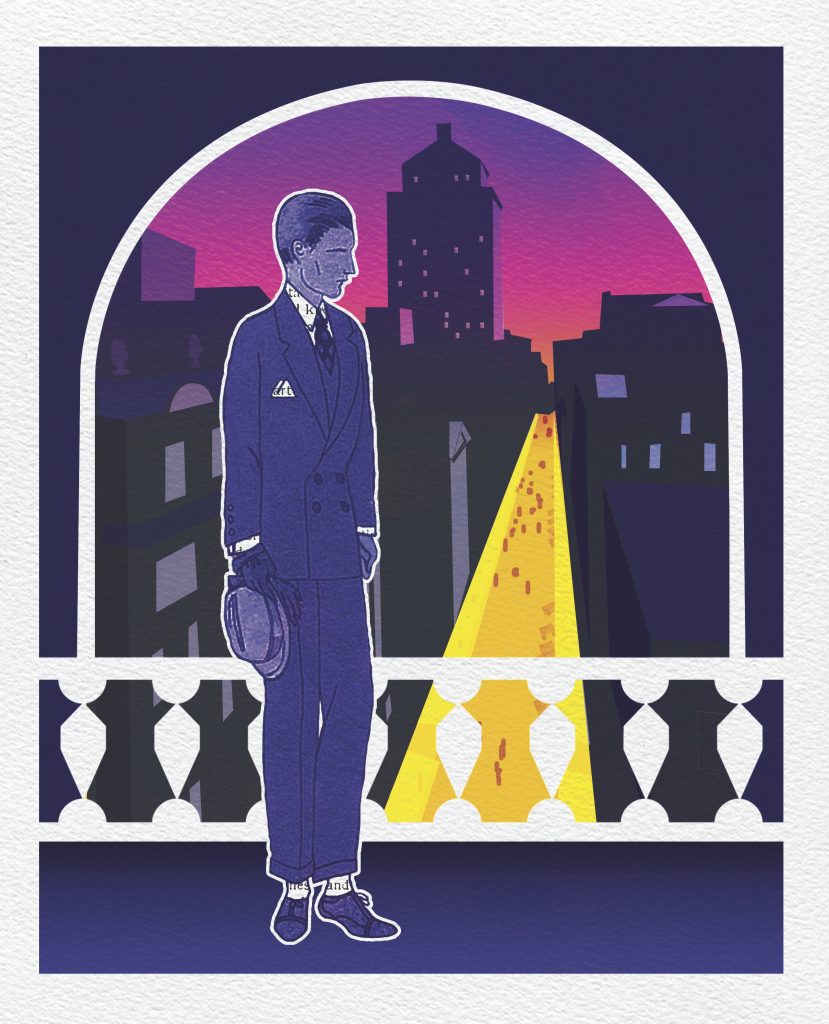

It was a desperate act by a “lonely young woman groping toward her kind” but the gambit paid off.3 A flood of responses led to a meeting at Gidlow’s house, a motley crew of writers, housewives, and assorted bohemian individuals. Among them was the “most astonishing, elegant being” that Gidlow had ever seen: a 19-year-old editorial assistant named Roswell Mills who was to become her closest friend and creative partner.4

When Gidlow reflected upon her life in Montreal decades later, it was always her friendship with Mills, that she remembered the most fondly. An elegant, quick-witted and openly gay reporter with the Star, Mills was perhaps one of the first people who Gidlow ever met who could match her mind, and more importantly, who could recognize who she was.5 He had sensed in Elsa a “lesbian temperament,” nicknaming her Sappho because she was “strong and independent like her, and a true poet.”6

Elsa Gidlow’s writing is the most significant insight into LGBTQ+ culture in the city.

Roswell made Gidlow his confidante, and personal project, supplying her with clothes and bringing her to plays and operas that Elsa couldn’t afford on her own salary. He taught her about alternative cultures and queer history, introducing her to the likes of Wilde and Baudelaire, the “bourgeois-scorning, decadent rebels” whose “glamorous sinfulness and metaphysical retreat from middle-class living” delighted the student.7 The two bonded over their shared outsider status in a rigidly heteronormative world, spending hazy days in an apartment on McGill College Avenue, merrily smoking and arguing into the small hours. Gidlow’s writings from that time paint a heady picture of rebellious youth, an intimate snapshot of queer Montrealers a century ago. She had found her people: those who she could “enjoy, converse with, learn from, and perhaps love.”8

Still, she found herself disappointed with Montreal’s scant lesbian scene. Prior to meeting Mills, Gidlow’s dalliances with women had been limited to one-sided longings with straight friends, and while she declared later in life that she had “been a lesbian all my life and a feminist since 12 or 13,” it was undoubtedly Mills who pulled her into Montreal’s queer milieu.9 Her first lover was an older bisexual woman named Marguerite Desmarais, a professional pianist who lived in a sprawling, sophisticated apartment in an uptown mansion, and treated Gidlow as a plaything. Eventually growing tired of playing second fiddle to Marguerite’s boyfriends, Gidlow had a second affair with an equally unsuitable woman: the married Estelle Cox, who never saw her as a true partner. Heartbroken, Gidlow maligned Montreal as a “desert of men” and a “women’s wasteland,” wondering, “were there in the world any other women like me—since Sappho?”10

In the backdrop of Gidlow’s angst-ridden love life was the shadow of the First World War, a constant presence through her and Mills’ adolescence. They were self-identified anarchists and pacifists, hating everything that the war represented, but particularly the self-indulgent nationalism of wartime propaganda. It spurred them on to start a newspaper in 1917, a mixed anti-war and cultural criticism periodical that featured their original editorials and poetry, as well of the works of people they admired. They called it Les Mouches Fantastiques, and entirely by accident, it was the first ever explicitly LGBTQ+ publication on the continent.

Les Mouches didn’t make waves in Canada, but was well received in the United States, where it had been informally distributed by their connections in the amateur press scene. It drew much praise and some criticism—the loudest of which came from science fiction writer and notorious conservative homophobe, H.P. Lovecraft.11 The pair only produced a short run of five copies, publishing the final issue in early 1920, months before Gidlow moved to New York. It was there that Gidlow wrote and published On A Grey Thread, her first full-length collection and the very first book of lesbian poetry in North America.

Gidlow never returned to Montreal, settling instead in San Francisco, where she lived out the rest of her (continually fascinating) life. Her works are stored in archives there, with few original materials (and no original copies of Les Mouches) residing in Montreal or Canada. She has been referred to on occasion as San Francisco’s or even New York’s Sappho, but the moniker relates strictly to her Canadian years; when a friend in New York referred to her as such, she replied “you mustn’t call me Sappho anymore… It belongs to my Montreal life.”12

Writer Hamish Copley notes that while there are records of LGBTQ+ life in Montreal from the 19th century, Elsa Gidlow’s writing is the most significant insight into LGBTQ+ culture in the city. Copley believes that Mills and Gidlow are Canada’s first gay and lesbian activists due to their work with Les Mouches, and that they are certainly two of the earliest gay figures whose lives are so well documented. Their friendship is an unusually clear picture of queer platonic love in the early 20th century, and they remained in touch until Mills’ death in 1966. The love and esteem that they felt for one another and all of their shared creative endeavours is a sweet reminder that queer friendship, collaboration, and solidarity stretches back hundreds of years, even if it is largely missing from our history books.

- Gidlow, Elsa. Elsa, I Come with My Songs: The Autobiography of Elsa Gidlow. Booklegger Press, 1986, pp. 34.

- Gidlow 58.

- Gidlow 68.

- Gidlow 69.

- Copley, Hamish. “Elsa Gidlow’s Circle – Roswell George Mills.” The Drummer’s Revenge, 2010, https://thedrummersrevenge.wordpress.com/2010/06/01/elsa-gidlows-circle-roswell-george-mills.

- Gidlow 72-75.

- Gidlow 71.

- Gidlow 72.

- Gidlow, Elsa. “Reviewed Work: Look Me in the Eye Old Women, Aging and Ageism by Barbara Macdonald, Cynthia Rich.” Off Our Backs,

Vol. 14, No. 5, pp.18, 1984. www.jstor.org/stable/25775109. - Gidlow (1986)122.

- Faig, Jr., Ken. “Lavender Ajays of the Red-Scare Period: 1917-1920.” The Fossil, Vol. 102, No. 4, 2006, pp. 7, http://www.thefossils.org/fossil/fos329.pdf.

- Gidlow 131.

Show Comments (0)