Statements like “When you defend yourself, you defend us all” and “When in doubt, become a widow” have become all too common on Hispanic feminist Facebook pages. In Latin America and the Caribbean, regions with the highest female homicide rates in the world, predators take women’s lives with impunity.1 Almost 98% of reported cases end with perpetrators going unpunished and unprosecuted.2 In response, women have begun to mobilize ever more visible online resistance strategies to counteract the deadly effects of sexism and misogyny in the region. These women engage in forms of online feminist activism, using social media as an important communication resource to advocate change.

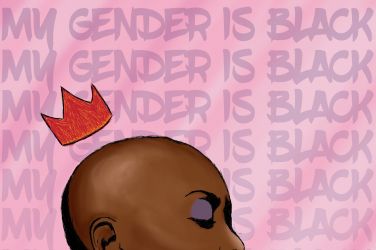

Over the past few years, Facebook has become instrumental in disseminating feminist initiatives. Hispanic Facebook users have spread short catchphrases that promote feminist principles and suggest responses to expressions of violence against women. These sayings have quickly developed into internet memes. A meme is a collection of digital content, usually an image and corresponding phrase, that spreads quickly around the web in various iterations and becomes a shared cultural experience.3 The term, derived from a combination of the Greek root mimeme (“something which is imitated”), the French word même (“same”), and the English word gene, reflects the way in which feminist slogans are widely shared and recreated through social media. Meme assertions like “Streets are mine in the morning and at night”, “Space is public, my body is not”, and “With or without clothes, my body is not available for you to touch,” as well as bolder declarations like “If he doesn’t respect you, make him feel scared”, “If guys know how to rape, girls should know how to kill”, and “Machete against the machote” remain common examples.4

Facebook has become instrumental in disseminating feminist initiatives. Hispanic Facebook users have spread short catchphrases that promote feminist principles and suggest responses to expressions of violence against women.

Such feminist memes circulate online to promote bodily autonomy and radical politics of self-defence. Gendered violence is a leading cause of death among women ages 15 to 44 in Latin America.5 Of the twenty-five countries worldwide with the highest rates of female homicide over the last decade, fourteen are located in Latin America.6 In fact, growing rates of murdered women in Hispanic countries has led to the coining of the term femicide, a conjunction of the terms female and homicide, to describe this unsettling phenomenon.

The feminist agenda in Latin America is deeply marked by this issue, as it has become a priority in feminist discourses, politics, and direct action. Activists in the region argue that brutal expressions of gendered violence are rooted in the objectification of women’s bodies, which have long been regarded as objects of public scrutiny and non-consensual use. Coupled with other global feminist concerns, like rape culture, a main issue for Latin American feminists is the underlying assumption that women’s bodies are available for other individuals to observe, judge, abuse and assassinate. It is in this context that feminist slogans are created and disseminated.

Many of these phrases, which originated from the graffiti slogans and protest signs used in site-specific street interventions, were recreated by other feminist activists and adapted for Facebook. For instance, the slogans “When you defend yourself, you defend us all”, “Space is public, my body is not”, and “Streets are mine in the morning and at night” were collectively written in Mexico City during the sixth annual International Anti-Street Harassment Week 2015. The “Re-appropriation of Public Space against Sexual Street Harassment” workshop, held at the event, encouraged participants to share their personal experiences with issues of safety in public spaces and develop seven short phrases that encapsulated their feelings toward the harassment they experienced when navigating the city. The group then carried out a street consciousness-raising performance where they chanted and wrote the phrases on protest signs. While not all of the slogans were created from scratch, some were based on well known lines within feminist circles and pre-existing discourse, the writing dynamic of the workshop enacted the same kind of collective processes that have resulted in the creation of feminist memes online. Whether online or offline, slogan-forming writing exercises allow for points of encounter where women can exchange their impressions and summarize their standpoints.

Feminist memes are thus a form of statement-and-claim-making that deploy linguistic resources (like rhyme and the paronomasia) and are inspired by contemporary gendered lived experience and embodied perceptions of everyday risk and hostility in city spaces.7 Through the benefits of the meme’s contagion and repetition, as well as the internet’s connective action, Hispanic feminist memes that respond to issues of safety enable the online circulation of specific feminist ethics, such as the caring for oneself and others, the mobilization of grassroots politics that characterize Latin American feminist struggles, and the taking part in dynamics of community building and affective networks of solidarity and action.8 These memes simultaneously remain in conversation with global feminist discourses, where slogans like “No means No, whatever we wear, wherever we go”, “Just because I move through public space doesn’t mean my body is public space” and “You rape, we chop” are commonly found in demonstrations and campaigns in other countries.

As part of an emerging tradition of political memes that do not only seek to be merely humorous or entertaining, online feminist memes make gendered violence visible and serve as a call to action to combat misogyny within a participatory environment. Despite the rise in recorded sexual assaults and of murdered women worldwide, misogynistic policymaking prevails and continues to strip women of the right to make decisions with regard to their own bodies. Within such a fraught political landscape, feminist memes combine the political with ethics of individual and collective action to stimulate politicized awareness, mobilize pivotal emancipatory discourses and highlight, what is inevitably, a matter of survival.

- NU Mujeres, “ECLAC Warns About High Number of Femicides in Latin America and the Caribbean”, Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean, 24 Nov 2015, http://www.cepal.org/en/pressreleases/eclac-warns-about-high-number-femicides-latin-america-and-caribbean, (accessed 26 Jan 2017).

- Luisa Carvalho, “Prevent Conflict, Transform Justice, Ensure Peace,” BBC News, 21 Nov 2016, http://www.bbc.com/mundo/noticias-america-latina-37828573, (accessed 30 Dec 2016).

- Limor Shifman, Memes in Digital Culture, (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2014), http://site.ebrary.com/lib/mcgill/reader.action?docID=10776345, (accessed 3 Dec 2016).

- Machote: chauvinist man.

- World Health Organization, “Media Center, Women’s Health,” Fact sheet N°334, updated September 2013, http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs334/en/, (accessed 30 Dec 2016).

- Argentina, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras,and Mexico rank at the top.

- Paronomasia: A play on words that sound alike.

- Jussi Parrika, “Contagion and Repetition: On the Viral Logic of Network Culture,” Ephemera, Theory & Politics in Organization, Volume 7, no. 2 (2007), 288.

Show Comments (0)